Daicon Film's “Aikoku Sentai Dai Nippon” Controversy & The Otaku Dawn

Or, a way-too-deep analytical exploration of a niche culture war drama from the early days of the Gainax crew

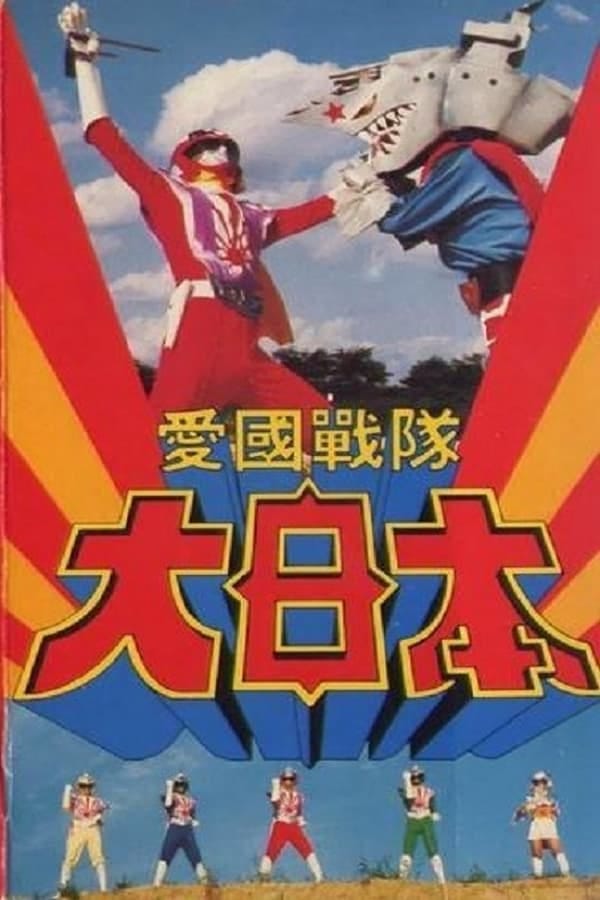

As I think many know, the people at Studio GAINAX did not start out making films as GAINAX. Before they had the funding to be a proper studio, they were “Daicon Films”, a somewhat-loose hobby group making fan films for the convention circuit and the wider indie scene. Most famously they made “Daicon IV” - the best music video of all time - but they also made live-action tokusatsu fan films. Hideaki Anno was a gigantic Ultraman fanboy and lived the dream of making his own fan film casting himself as Ultraman, but he wasn’t the only one directing films there. In 1982 Toshio Okada, co-founder of Gainax and the legendary ‘Otaking’ himself - though at this time a convention organizer and founder of an animanga merch store “General Products” - lead the making of a 15 minute parody tokusatsu “Aikoku Sentai Dai Nippon/Patriotic Squadron Great Japan”1, where the titular squadron fight the evil USSR Red Bear Empire to save Japan.

And it honestly kind of slaps? The Empire is led by the “Death Kremlin”, amazing name, and the heroes are all named silly Japanese cultural references - the token girl is called Ai Geisha because subtlety is for losers. Scenes include the Red Bear Empire trying to indoctrinate Japanese youth by shipping them books that are just blank red paper:

The minions of the Empire being beaten by our heroes flashing them an invoice for 8 million yen these commies could never afford:

And a final battle against our main battleship-headed monster where our heroes do a samurai slash in the shape of the crest of Mt Fuji and blow it up to defeat him:

This is real deal kino kitsch, I am absolutely here for it. It is not currently subtitled the best I can tell, and of course probably never existed in any quality above “rescued from 2008 Youtube’s garbage disposal”, but if you look beyond that it is very lovable. The film is a fun Cold War Sentai comedy, and it aired at the “TOKON-8” SF convention to great success - it had several rescreenings at other cons, high home video sales, and even a run at local film awards2. Dai Nippon was a true crowd pleaser.

Well, mostly.

“Xenophobic Propaganda”

I should say up front that this essay isn’t quite a project of grand original research - instead when researching the topic I stumbled upon the Japanese blogger “Kensyouhan” who had done most of the gruntwork for me in a four part essay series, citing the majority of the the original primary documents3. Which is great for me, no need to spend hundreds of dollars importing & scanning 1980’s doujin circle magazines and the like. I am here translating their writing into an English-accessible audience, bringing in a few more sources, and adding context & analysis - valuable work, but I don’t want to steal any valor.

Anyway, shortly after TOKON-8 the SF fanzine “Iskateli” published a con review article by Hatsu Hiroaki4, and it ended with a quite merciless review of Dai Nippon5:

Many participants, especially the members of Iskateli were left pale-faced by the final item on the program. It was an 8mm film produced by the Osaka-based commercial group "General Products titled "Patriotic Task Force Great Japan".

Judging by the title, one would expect it to be a delightful parody mocking the Japanese state. However, the content turned out to be an astonishingly low-level piece of xenophobic propaganda, and unbelievably, the creators earnestly shouted "Long live the Empire of Japan."

By the way, you filmmakers from General Products, just about forty years ago, the unimaginable mass slaughter of Asians by the "Empire of Japan" took place, the same one you so fervently wish to be reborn seven times over in this film. Whether the creators are professional right-wingers or this film is the product of sheer ignorance, I do not know, but to expose such shame to the world at their age is beyond belief. Perhaps it would be for the best if they focused themselves fully on their merchandise business instead.

Article going as hard as its cover does! Hatsu was a con organizer at TOKON-8, and ran the panel where the film was screened. Normally the films are pre-screened for issues, but the Daicon crew didn’t deliver Dai Nippon to the con until the day of, preventing it from being reviewed - a start of a long tradition of censorship-evasion-via-last-minute-deliveries for Gainax6! As you can imagine, for Hatsu this made the film a personal issue.

While this tone isn’t unheard of for fanzine discourse back in the day, it is still at the edge of the bell curve; it and Dai Nippon soon became the talk of the SF community. What proceeded was a stream of back-and-forths from the crew at Iskateli, the creators of Dai Nippon over at Daicon Films/General Products, and other commentators who jumped in. Toshio Okada himself definitely fanned the flames in a conversation with future GAINAX co-founder Yasuhiro Takeda, with responses unsparing in their sarcastic disdain for the critique7:

Okada: "The great thing about the sci-fi convention is that even if we make a movie like Dai Nippon, no one gets angry, they just laugh along with us. In other circles, there would definitely be some oversensitive brat, veins bulging in their forehead, who would rage and scream…”

And in a follow-up:

Okada: "But, you know... Yeah, at this point, we have no choice! Takeda-san, let's make a new film!"

Takeda: "What's it gonna be?"

Okada: "The title will be 'Communist Task Force Chinese Noodles'! It's about characters like Ai Marx and Ai Lenin protecting the people from the evil clutches of the imperialist 'Killer Pentagon.' If we make this, do you think it might finally appease this Hatsu person?"

Takeda: "No, I'm not sure. They might say it's another 'astonishingly low-level piece of xenophobic propaganda' or something. I really thought there were no people like this in the sci-fi community..."

Okada: "At the last screening in Osaka, even a boy in his second year of middle school warned us, saying 'If people with low standards or elementary school kids see it, they'll think it's a right-wing film.' Well, I guess it just proves 'Sturgeon's Law' is still alive and well8. Ah, how ridiculous."

Okada even went so far as to include a comic mocking the staff of Iskateli in “The World of Daicon Films Vol 1”, their first art & production book for the films they were making:

You don’t need a detailed translation here, they are calling them a bunch of idiots.

There were of course responses from the Iskateli circle, and the whole thing sort of exploded out from there. Other commentators weighed in; academics from nearby universities even published articles about it; at one point Akio Jissogi, director of Ultraman among many other works, saw the film and gave out a take. We even have a healthy dose of reader letters from the various magazines sharing their opinions, one of which - from over a year after it aired - I will include because I just love it9:

The article in General Protoculture is truly disappointing. I was moved, believing that the creators of "Patriotic Task Force Great Japan" were true patriots, genuinely concerned for the future of Japan. But to call their painstaking work a joke in response to those commie protests!! If it was a joke from the start, then immediately renounce the name "Patriotic Squadron Great Japan"!!

[…] Admit your mistake, and even now, correct it and apologize to the Japanese people, no, to His Majesty the Emperor. If there is no indication of this, we will take appropriate measures.

To be clear they are almost certainly joking - trolls exist in every generation!

Now that I think it is well established that within this tiny world of indie SF filmmakers this became the “topic of discussion”, I don’t think going through the timeline of articles is worth the trouble. It doesn’t go anywhere, obviously - people just argue back and forth, Daicon IV comes out in 1983 which puts the Daicon crew on a trajectory to more impactful work, and all of this fades away by the end of 1984 into a “man people were crazy back then huh” memory.

Instead, I think the details of this controversy are revealing of wider trends - why it happened to begin with, and what it shows about the changing culture of “otaku” spaces in Japan at the time.

From Frankfurt to Tokyo’s Sci Fi Dreams

So to start at the object-level, does this critique have any merit? From our position as outsiders, not truly; the film is very provocative but in the end brazenly unserious, in a way that makes holding it to any serious political beliefs difficult to stomach. This is media, it’s subjective of course, but it seems like a drama-for-the-sake of it moment clashing with big personalities10.

But critics like Hatsu didn’t really see media-as-media - in this era the SF community was highly political, and art-as-activism loomed large among leading figures in the scene. Which, in 1982, many saw as activism over very real threats, and the domains of art & media as core to those threats. In another of their columns in Iskateli, Hatsu elaborates on this in relation to Dai Nippon11:

Today, the atmosphere of totalitarianism is certainly spreading even in the "SF fandom," which is not disconnected from wider society. In the case of “controlled fascism”, or to borrow Heinrich Böll's expression, "welfare state martial law," this soft fascism (which is actually the typical kind of modernist and futurist totalitarianism that SF has consistently depicted and denounced) is the true substance of totalitarianism.

[…] When the nightmare that has been depicted in the imagination is about to become reality, what is required of SF writers above all else is a cold-hearted recognition of reality and a strong criticality. We cannot deal with the coming of all-out controlled fascism by ignoring the immediate danger.

Which for sure is a lot of graduate-seminar-students-three-drinks-in-at-the-pub energy, I will spare you a detailed explanation, but “controlled fascism” as a concept is key. You have heard of it before of course, market capitalism & consumer goods as an opiate for the masses to shift their values such that they can no longer notice the expanding edifice of control - not just by the state, but by an enmeshed system of state & private actors, a system too big to fight and too diffuse to target that placates the center while tearing apart the periphery.

This era is the tail end of the dominance of the “Frankfurt School” of critical sociological theory in artists, on full display here - a collection of mainly German sociologists writing in the shadow of the fascist regime they lived through. And, let’s be clear here, this is 1982 - the Vietnam War just happened, the war in Afghanistan is revving up, and Cold War mutually-assured-destruction is still floating around, ever-present. Meanwhile Japan is the epitome of a “passive observer” in that process, benefiting from a global order but perhaps oblivious to its risks and costs. So yes, these people have a very “wake up sheeple” energy, but you can see how there are maybe things out there to wake up to. And since consumerism is the vessel, policing media is the natural defense - things like Dai Nippon sanitize and normalize the right-wing status quo by making the horrific comedic. Or that is what they claim, at least.

At one point, Okada & crew do a follow-up panel at another SF conference where they mock their critics and even do a dance they lead the audience in that is I think a mocking reference to atomic bombings12, which inspires another round of accusations of disrespect - certainly a good chunk of this drama stems from how much Okada rage-baited his critics. Most importantly, it produces this comic of them doing the dance13:

Which is extremely cute. But additionally, among the spate of angry letters from attendees was this woman14:

The shock I felt when I saw [the dance] at the SF convention…!

What I felt was anger.

I was born and raised in Nagasaki, and my mother is a survivor of the atomic bomb. Do you understand? From an early age, I saw my classmates die of leukemia and relatives suffer from radiation sickness. Although it has been almost 40 years since the bombing, this tragedy is not "the past." At least, not for me.

I won’t pretend that this isn’t hyperbolic - but her feelings are real. Other letters around this compared Dai Nippon’s use of military symbols from wartime Japan to the Nazi swastika; you can see how this entire thing dovetails right into an ongoing culture war over how much Japan has “owned up” to its crimes in World War Two that is still unresolved today. For all of these people, the stakes around this dumb fan film were important - the SF community had loftier aspirations than this kind of content, and Okada was mocking them for said aspirations.

There is a common term relevant to this time period - Okada name-drops this specifically at one point15 - the “Anpo Generation”, named after a huge wave of protests through the 1960’s against ostensibly US military bases in Japan but really a whole host of left vs right political issues. Like so many countries, 1960’s era protests in Japan birthed a generation of intellectuals & artists who believed in radical social change and the value in their work to achieve that. The zeitgeist of “high” art in 1970’s Japan was very much led by the Anpo Generation, and that included manga artists and even anime figures. For people like Hatsu, this was what “SF” was about.

Or at least what they wanted it to be about - but that community was changing fast.

Gatekeeping the New Anime Century

Something that comes out in so many of the documents is a focus on international audiences - it is not that this fan film is being aired at all, but that it is being aired where westerners can see it16:

First, please explain to me why it is right to invite John Branagh, the leader of the British anti-nuclear movement, and the Italian pacifist writer Rino Aldani, and then [dance a silly dance] in front of them?

And17:

In order to no longer be a "nation without remorse," let's make them apologize for screening "Dai Nippon" at TOKON! […] For being shown at a science fiction convention and thus undermining internationalism.

At one point one of the crew of the Iskateli publishes an article to the Dutch SF magazine Shards of Babel18 discussing the controversy. Of course, no one in Europe would have seen Dai Nippon! They would have no ability to. But the SF community overall viewed itself as part of an international movement; some of the biggest draws at any of these events were often the foreign authors they could nab as guests and panelists. Japanese creators would often try to make works that matched the artistic trends of the international scene.

And honestly, they saw themselves as too international - it was aspirational & rooted in a sense of inadequacy in a lot of ways. The West had all the power, all the money, and all the “real” artists made their mark there. This comes up a bunch in the history of early animanga - a work trying to get “true” success by pursuing some sort of international success. Many Japanese artists of course found some of that success, but overall it is fair to say that by the 1980’s the number of Japanese artists of any stripe that truly “broke out” in the west was low.

Daicon Films was, of course, completely uninterested in any of that. They liked foreign works well enough, but tokusatsu was a Japanese medium in so many ways, making minimal or no attempts to succeed overseas. It was succeeding with domestic Japanese audiences, at scales the writers of high-concept political SF could never dream of. Toshio Okada’s type were chasing a new type of success with a new type of fanbase - and he called out his critics for gatekeeping that reality19:

The sci-fi world is in a bad state right now. If we take a narrow view of science fiction and say that we don't approve of anime or special effects, we'll be in trouble.

We need to bring those stubborn, over-thirty types to their knees. We can get all the young sci-fi fans on our side.

And here is his co-creative Yasuhiro Takeda20:

There may have also been an aspect to this where people who had not been happy with our activities seized this opportunity to attack us. This is because we were taking up tokusatsu films and anime, which old-school sci-fi fans tended to dismiss by saying, "This is not sci-fi!", and saying in response "This is sci-fi too”.

Okada also had this whole “Tokyo elites vs blue-collar Osaka folk” thing going on, which fell along the same general axis. And from most metrics, the Okada side rode with the times here. The Nihon SF Conference (of which TOKON & DAICON were individual instances) in the 1970’s averaged ~500 people, and often had less. In 1980, as the first real anime boom was in full swing, it had 1300 attendees; at the infamous DAICON IV, it had 400021. New crowds were entering the scene, and they cared about Gundam and Ultraman a good deal more than Asimov and the Frankfurt School. What the critics of Dai Nippon never dispute, and all the sources confirm, is that when the film aired or when Okada did his little dance, the audience in attendance was loving it.

In short, the Anpo Generation was fading. The first crop of creators were coming of age who weren’t there for the Anpo protests and that entire movement, and didn’t particularly care about their causes. It was a new generation; unconcerned with their issues, their internationalism, their activism.

On February 22nd, 1981 the freshly-airing Mobile Suit Gundam made a “movie version” of its first 13 episodes, and held a special promotional event at a cinema in Shinjuku, with creator Yoshiyuki Tomino appearing to host the event. The attendance vastly exceeded expectations, reaching 15,000 people. In his (pre-planned regardless of crowd size) speech to the crowd of fans of this new kind of anime, Tomino declared the “Anime Shinseiki Sengen”, or “New Anime Century”, predicting that otaku present would be the future of culture22. Marketing flair from top to bottom, but he was right in hindsight - the event would become a stand-in for the birth of otaku. Toshio Okada’s Daicon/General Pro outfit would make its start selling Gundam model kits, making them the perfect ambassadors for this cultural change. The fight around Dai Nippon, which aired the next year, is I think perfectly symbolic of that generational shift. Hatsu and his types were, through their criticism of its crassness and “right-wing politics”, attempting to hold back the tide of change in their own community. And they would lose.

Or, as Hatsu himself put it, lamenting his own defeat23:

Nowadays, everyone and their cat reads “sci-fi”… Even at sci-fi conventions, if four-digit numbers of people gather, surely two-thirds of them are simply fetishists of this or that character or so-called "sci-fi fans" who are only slightly more sophisticated.

So I find this event interesting in its own right, certainly, as a piece of historical trivia. But I think you can find it a lot of themes of the rise of otaku culture in 80’s Japan, all condensed into one little piece of dumb fandom drama.

Which, uh, I think is neat I guess? Hopefully after that much text you do too!

Link to the version with the bonus production footage, which for something like this is indelibly charming. I believe Hideaki Anno & Shinji Higuchi worked on the visual effects side of the film, and Anno was maybe the narrator but I didn’t see a reliable citation for that.

It even “won” the Best Film category for Seiun Awards, SF Japan’s oldest, but the judges disqualified it as it wasn’t “professional” per their rules and gave the award to Blade Runner instead. Which, beating Blade Runner is quite a testament to its popularity! (Shards of Babel 12, January 1984)

He was one of the founders of the magazine and has had long career as a culture writer; and is still around today - here is his beautiful 2000’s-era website if you want to learn more.

Iskateli Vol 24, December 1982

To explain the joke, Evangelion episodes were often delivered to the broadcaster at the last minute, preventing the station from censoring any of its violent and sexual content (or so some say).

SFism [SFイズム] Vol 8, March 1983

Their column in SFism was called “Sturgeon’s Law”, so this is a reference as well as invoking the point. Theodore Sturgeon was an SF author who coined the law in the 1950’s, so this was a known term in the global SF community at this time.

SFism Vol. 9, January 1984

A mistake our civilized culture of today would never possibly make about media, of course.

Iskateli, Vol. 25, December 1983

The dance is called the “Pikadon Ondo/ピカドン音頭”, and pikudon is a common term for the atomic bombs as an onomatopoeia of its explosive sound. Not-really-related but here is Hideaki Anno doing an illustration involving the dance around the same time.

From “DAICON III After Report”, reprinted in Toshio Okada’s "The Great Monster of the Century!! Toshio Okada’s Unreleased Stories" , East Press, July 1, 1998.

SFism Vol.7, July 1983

Testament by Toshio Okada, 2010. He calls them the “Zenkyoto Generation”, named after the main leftist student groups involved in the 1968-1989 Japanese University Protests, but it is the same concept.

Iskateli, Vol. 25

Iskateli, Vol. 26, July 1983

As mentioned before, Shards of Babel 12 for the specific volume - with a follow-up in Shards of Babel 20. You can find some of these magazines archived here.

Testament, Toshio Okada

“Nootenki Tsuushin" Column, Wani Magazine [Year Unknown]

Photo credit - and if you care to learn more of this event - from Pure Invention by Matt Alt

Iskateli, Vol 25

It's amusing to me the attitude Hatsu seems to have to stuff like Gundam as crass, unserious, commercial stuff based on this article (at least, from what I'm inferring). Whatever else one might say about Tomino's Gundam stuff, I'd never say it's uninterested in saying stuff about politics. It's not that Gundam is NEVER crass, unserious, commercial, too driven by model kits, etc. But that doesn't seem to prevent it from also being treated as "serious sci-fi", at least from my perception of things.

Fantastic read!